In July 2022, the East Sussex Pension Fund commissioned a report on the relative merits of divestment vs engagement.

Last week a summary of this report – which may have cost the Fund as much as £50k to produce – was finally placed in the public domain.

Judging by this summary, the report appears to have been a significant missed opportunity: re-hashing long-refuted arguments; taking industry claims about engagement at face value; chasing red-herrings; misrepresenting divestment; and ignoring crucial evidence.

Nonetheless, it also appears to have (almost accidentally) shown that fossil fuel divestment – at least when understood in the sense that campaigners have been using it for the last 12 years – would be fairly straightforward for the Fund to implement and would have no significant negative repercussions for the Fund’s overall strategy.

This situation has arisen because, despite a ten-year-long campaign, the Fund and its advisers have consistently failed to take on board: (a) what divestment campaigners have actually been calling for; (b) why they’ve been calling for it; and (c) the time-frame for implementation that campaigners have been demanding.

As Upton Sinclair observed long ago: ‘It is difficult to get a [someone] to understand something when [their] salary depends upon [them] not understanding it.’

We examine some of these points in greater depth below.

But first, a reminder about definitions:

> Divestment: divestment campaigns seek to get institutions (such as pension funds, philanthropic funds and educational institutions) to make highly visible public commitments to ditch their investments in a company or set of companies. Such campaigns aim to undermine the ‘social licence to operate’ of the targeted companies, and thereby bring about government legislation against them.

> Engagement: shareholder engagement seeks to change the behaviour of a company (or set of companies) through (usually non-binding) shareholder motions at company AGMs, and dialogue with company directors. This is the current approach of the East Sussex Pension Fund when it comes to fossil fuel companies.

Now we look at six key points about the summary (all page number references refer to the Summary, as it appears on pages 205 – 242 of the public reports pack for the 19 September 2023 Pension Committee meeting):

1. The summary simply *assumes* (without evidence) that engagement has an important role to play in addressing the climate crisis, taking industry claims at face value.

For example the summary states that: ‘Focussed engagement by asset owners will be important to hold companies to account’ (p. 221).

In reality, as Ellen Quigley (from Cambridge University’s Centre for the Study of Existential Risk) has explained ‘responsible investment in its current guise is not fit for purpose as a means to address systemic risks – particularly climate change’. [1]

Indeed, she notes, it has ‘met with manifest failure. Emissions have continued to grow unabated; climate risk to the real economy has increased. ESG appears to have resulted in no genuine change in company behaviour’.

The summary does grudgingly acknowledge (p. 220) that: ‘The attribution of climate action gains to make the case for engagement activity remains difficult to demonstrate’.

However, this is a significant understatement.

Indeed, despite many years of engagement not a single major oil and gas company is currently on a 1.5ºC compliant pathway (though some have made non-credible non-binding claims that they will do things so as to intersect with such a pathway in the distant future eg. around 2050). [2]

Finally, the Summary places undue credence on industry (ie. investment firms) claims about the virtues of engagement.

But the industry is clearly not a dispassionate analyst. Indeed, it has a vested interest in talking up engagement as it’s effectively a product that it is selling to customers like the East Sussex Pension Fund.

2. The summary fails to even mention the main rationale for divestment. Namely, driving ‘restrictive legislation’ against targeted companies through a process of stigmatisation.

As noted above, global divestment movements involve getting institutions to make well-publicised public commitments to shift their investments out of a set of companies. They aim to change government legislation and policy regarding these companies as a whole through a process of social stigmatisation – an approach with a proven track record.

Indeed, a 2013 study by academics at the University of Oxford’s Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment concluded that: ‘In almost every divestment campaign we reviewed from adult services to Darfur, from tobacco to South Africa, divestment campaigns were successful in lobbying for restrictive legislation affecting stigmatised firms.’ [3]

All of this was explicitly stated and referenced in a letter from Pension Committee member Georgia Taylor, that was sent to the East Sussex Pension Fund’s head of pensions in late 2022. This information was then apparently passed to the reports authors – who seem to have chosen to ignore it.

3. The summary ignores critical evidence (eg. the track record of past global divestment movements).

See the commentary to point 2. above. Additionally, according to the UN’s lead negotiator on climate change between 2010 – 2016, Christina Figueres, the global fossil fuel divestment movement was ‘a primary driver of success at the Paris Climate Talks in 2015’.

There is also no mention anywhere in the summary of the five UK Pension Funds that *have* made full divestment commitments – or of the scale of the global fossil fuel divestment movement.

To date, over 1,590 institutions with a collective value of over $40.5 trillion have made some form of divestment commitment. [4]

4. The summary misrepresents ‘avoid[ing] the most deleterious effects of climate change’ as a non-financial, ‘quality of life’ issue, which the Fund is therefore free to ignore.

This takes place on pages 216 – 217 of the summary: ‘a desire to invest the Fund’s assets to ensure that Fund beneficiaries can live in a world which, for example, avoids the most deleterious effects of climate change is not a financial factor, but a non-financial one.’

However, in reality ‘avoid[ing] the most deleterious effects of climate change’ is an essential *financial factor* for the Fund.

Indeed, according to the Climate Action 100+ investor initiative (of which the Fund is a member): ‘action to cut [global] emissions and avoid the worst impacts of climate change is the only real path to protect long-term investment value and returns.’ (emphasis added) [5]

5. The summary uses definitions that inflate the Fund’s ‘Fossil Fuel Exposure’ and make it look harder for the Fund to divest than is actually the case.

See pp. 224 – 225 and 238 – 239, where the Fund’s ‘Fossil Fuel Exposure’ and ‘Fossil Fuel Extraction Exposure’ are defined and tabulated.

What the summary calls the Fund’s ‘Fossil Fuel Exposure’ – which includes not just fossil fuel companies but utility companies that use gas or coal, companies that transport fossil fuels etc… – is over five times higher than the Fund’s ‘Fossil Fuel Extraction Exposure’:

Compare these idiosyncratic defintions to the global fossil fuel divestment movement’s standard divestment demands, which are for an institution to:

a. Immediately freeze any new investment in the top 200 publicly-traded fossil fuel companies. [As determined by the most recent Carbon Underground 200 list published by Fossil Free Indexes: https://www.ffisolutions.com/research-analytics-index-solutions/research-screening/the-carbon-underground-200/]

b. Divest from direct ownership and any commingled funds that include fossil fuel public equities and corporate bonds within [insert agreed number of years given market forecasts].

Note that these demands:

– single out fossil fuel extractors, namely the top 100 coal and the top 100 oil and gas publicly-traded reserve holders globally;

– do not include private equity investments (this may have been deliberate, because of the sorts of financial penalties for early exit from such investments that are flagged in the summary)

– do not call for *immediate* divestment (a five-year process seems to have been a common commitment).

In other words, for campaigners fossil fuel divestment means divestment from ‘fossil fuel extractors’, not the massively-inflated category (‘Fossil Fuel Exposure’) used in the summary.

And the standard divestment commitment also doesn’t set a time-line for exiting existing private equity investments, though it would prevent an investor from making new private equity investments involving fossil fuel extraction.

6. The summary suggests that the Fund might actually be able to divest – in the sense that campaigners have long demanded – without leaving the ACCESS pool and with an impact on the Fund’s (short-term) risk-adjusted returns that ‘is relatively small in the context of the [Fund’s] overall strategy’.

The East Sussex Pension Fund is a member of the so-called ACCESS pool of pension funds, through which it shares a number of resources with a several other local government pension schemes. The aim of such ‘pools’ is to save money on the costs of investing.

Having artificially inflated the figure for the Fund’s ‘fossil fuel exposure’ (see 5. above) the summary then goes on to detail how ‘challenging’ it would be to divest from this set of companies ‘without compromising the investment strategy [of the Fund] in some way’ (p. 230).

Crucially, it claims that ‘[t]o pursue a full divestment policy the Fund will likely to look outside of the ACCESS Pool’ and that this could be expensive and lead to ‘possible government intervention’.

However, once we use the definition of fossil fuel exposure that campaigners across the world have been using for the last 12 years (see 5. above) things look very different.

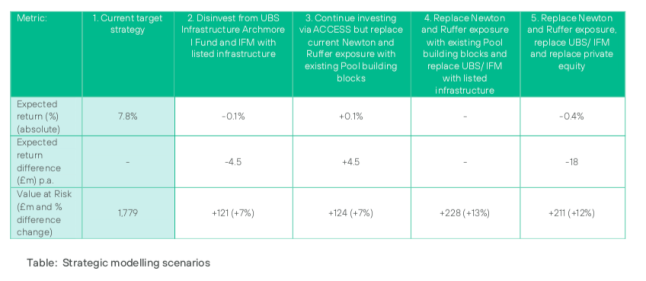

Indeed, a public commitment to fully divest from all ‘fossil fuel extractor’ public equities and corporate bonds within five years (while making no new investments in fossil fuel extractors) looks very similar to the scenario in column 3 of the Table on page 228 (‘Continue investing via ACCESS but replace current Newton and Ruffer exposure with existing Pool building blocks’):

Indeed, the only difference between the two options would appear to be the M&G Alpha Opportunities fund (see table on p. 225), which might be covered by such a commitment, but isn’t mentioned in column 3.

This is because, apart from Newton, Ruffer and M&G Alpha Opportunities, all of the Fund’s remaining exposure to ‘fossil fuel extractors’ is via private equity or the M&G Corporate Bonds fund (which the Fund is already in the process of exiting).

(Note also that the M&G Alpha Opportunities fossil fuel ‘extraction’ exposure currently stands at £1.6m or less than 0.036% of the total value of the Fund.)

Now the table above states that the column 3 option would slightly increase the Fund’s absolute return (+0.1%) while also increasing the Fund’s Value at Risk (a way of quantifying the extent of possible financial losses over a specific time frame – in this case the next three years) by 7%.

However, the summary also states that the column 2 option (‘Disinvest from UBS Infrastructure Archmore 1 Fund and IFM with listed infrastructure’) – which would actually slightly decrease the Fund’s absolute return while increasing the Fund’s Value at Risk by the same percentage as the column 3 option – would have only a ‘relatively small’ impact on ‘the Fund’s overall strategy’.

This suggests that option 3 – which could be implemented without leaving the ACCESS pool, and which is, in effect, the public divestment commitment that campaigners have long been demanding – would also only have a ‘relatively small’ impact on ‘the Fund’s overall strategy’ – at least in the short term.

On the other hand, this option – at least if made noisily and in public, as a commitment to divest from fossil fuels – should actually have a positive long-term impact on the Fund’s overall strategy.

This is because it would help to undermine the power of the fossil fuel industry, and thereby bring about the ‘restrictive legislation’ on fossil fuel companies necessary to avoid the worst impacts of climate change – which, as we have seen (see 4. above) ‘ is the only real path to protect long-term investment value and returns’.

ENDNOTES

[1] ‘Universal Ownership in Practice: A Practical Investment Framework for Asset Owners’, May 28, 2020. Winner of Best Paper for Potential Impact on Sustainable Finance Practices, GRASFI 2020. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3638217

[2] See eg. ‘Big Oil Reality Check — Updated Assessment of Oil and Gas Company Climate Plans’, Oil Change International, May 2022, https://tinyurl.com/bigoil2022. For a dismantling of the Transition Pathway Initiative’s Nov ‘21 claim that three oil and gas majors are now 1.5˚C-aligned see ‘The TPI benchmark: misleading approach, dangerous conclusion’, Reclaim Finance, Dec ‘21, https://tinyurl.com/misleadinganddangerous.

[3] ‘Stranded assets and the fossil fuel divestment campaign: what does divestment mean for the valuation of fossil fuel assets?’, https://tinyurl.com/smithschoolreport.

[4] https://divestmentdatabase.org

[5] ‘The Business Case’, Climate Action 100+, https://tinyurl.com/climateaction100